War memorial in Charlesworth

Their name liveth for evermore

Tracing the names on a war memorial

Memorials to the First World War are such an everyday sight in Britain that we take them for granted. Yet their names are a poignant reminder of the slaughter that devastated whole communities. A little research, using resources now available on the Internet, can bring both the history and the literature to life. There is a separate page on texts that have become associated with war memorials and Remembrance ceremonies.

The photographs here are of the memorial in the centre of my own Derbyshire village, passed daily by commuters, schoolchildren and anyone posting a letter or calling at one of the two adjacent pubs. In 1914, Charlesworth was a semi-rural community with factories, shops and farms; the war in Europe, let alone the Middle East, must have seemed a long way away. If you want to find local war memorials, try the UK National Inventory of War Memorials site; this has a good search facility that includes many of the names on the memorials.

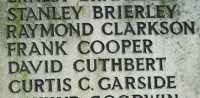

The photographs here are of the memorial in the centre of my own Derbyshire village, passed daily by commuters, schoolchildren and anyone posting a letter or calling at one of the two adjacent pubs. In 1914, Charlesworth was a semi-rural community with factories, shops and farms; the war in Europe, let alone the Middle East, must have seemed a long way away. If you want to find local war memorials, try the UK National Inventory of War Memorials site; this has a good search facility that includes many of the names on the memorials.Acting on a suggestion from Alf Wilkinson, I selected two names from the memorial that appeared distinctive. Garsides still have a furniture shop in Glossop and Brierley is another local name. A few minutes on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission site enabled me to trace both men; the results are in the panels. Curtis Garside, 22 when he died in what was then called Mesopotamia (now Iraq), came from the George and Dragon Hotel immediately opposite the memorial. How sharp a reminder must the erection of the war memorial have been for his parents! Stanley Brierley left a young widow in Chisworth, just a short distance down the road.

Private, 8th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

Died age 21, 17 September 1917

Son of Joe Brierley of 11 Hambleton Street, Wakefield; husband of Betty Brierley of Holehouse, Charlesworth, Broadbottom, Manchester.

Memorial: Panel 125 to 128, Tyne Cot Memorial

Curtis C Garside

Private, B Company, 8th Battalion, Cheshire Regiment

Died age 22 on 12 June 1917

Son of John and Jessie Garside, of George and Dragon Hotel, Charlesworth, Derbyshire.

Memorial: Baghdad (North Gate) War Cemetery

Local troops are still dying in Iraq; 19-year-old Jamie Hancock, whose mother lives in Glossop, was killed in Basra in 2006.

George and Dragon Hotel and War Memorial

'Their Name Liveth For Evermore' is a line in the Apocryphal Book of Ecclesiasticus, from the well-known passage beginning 'Let us now praise famous men' which is sometimes read on Remembrance Day. You can see it inscribed on the memorial in Broadbottom here and read the whole passage on the page entitled 'We will remember them'. It was selected as an appropriate inscription for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission by Rudyard Kipling, himself devastated by the death in 1915 of his only son John just six weeks after his 18th birthday. Kipling had to use his influence to have John accepted into the Army despite his appalling eyesight. Perhaps this explains the bitterness of 'Common Form', one of his Epitaphs of the War (you can read them all here). Was he including himself in the indictment?

If any question why we died,

Tell them, because our fathers lied.

Well might the Dead who struggled in the slime

Rise and deride this sepulchre of crime.

Charlesworth and Chisworth in the early Twentieth Century

For information about life in Charlesworth and Chisworth around the time of the First World War, see the extracts from Kelly's Directory of 1891 on the Andrews Pages: 'Cotton spinning and rope and cotton band making are carried on here. Lord Howard of Glossop is lord of the manor and the principal landowner'. 'The Reminiscences of Mrs Hannah Bocking' from Chisworth on Marjorie Ward's North West Derbyshire site provide insights into life in the semi-rural community in 1917. 'In the valley below... was Lee Valley Bleach Works known locally as Bone Mill, this was making gun cotton for the war.... The old people spoke in the local dialect, thee and tha, canna, munna, shauna, and dunna.'

Acknowledgement

This project uses an idea suggested by Alf Wilkinson in an article in The TES on 12 January 2007. Alf's site for history teachers is Burnt Cakes.